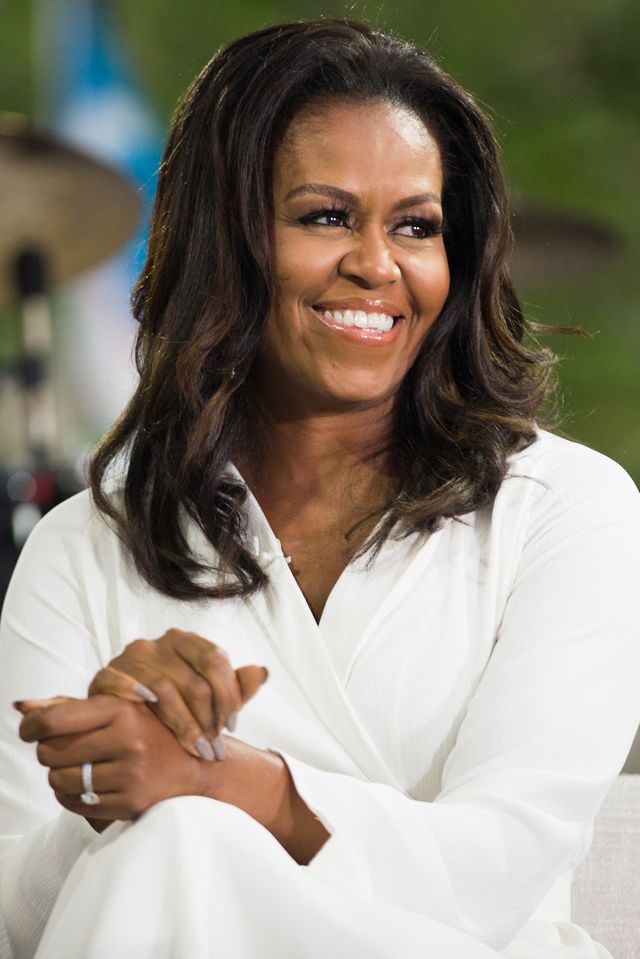

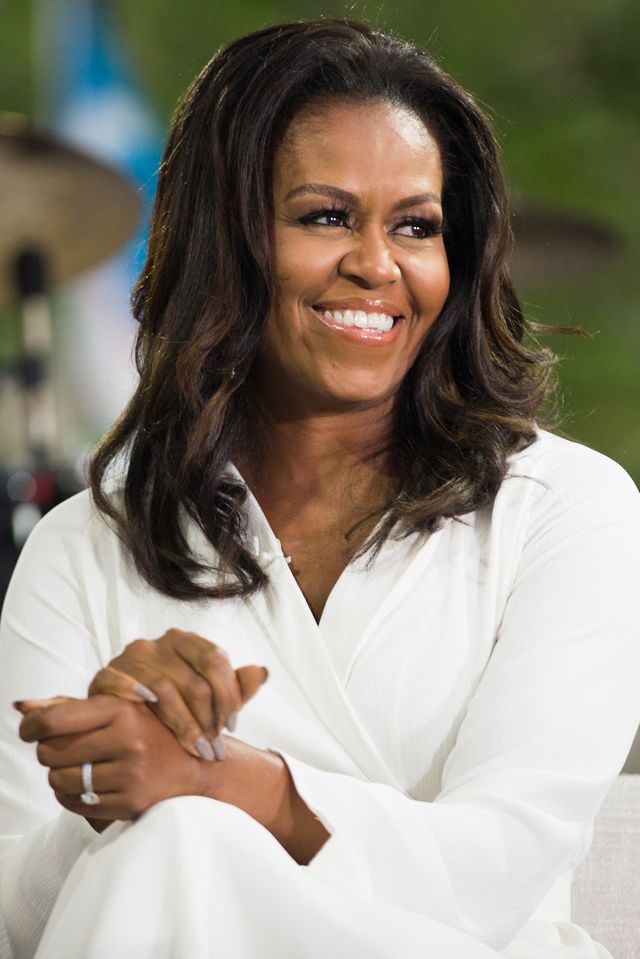

In her new book, the former First Lady writes about her mother's love.

Published: Nov 12, 2018 6:00 AM EST Save Article

Our editors handpick the products that we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page.

When Michelle Obama first announced she was releasing her memoir, Becoming, last year, she promised that she'd open up about her roots—"and how a little girl from the South Side of Chicago found her voice and developed the strength to use it to empower others."

In this exclusive book excerpt for OprahMag.com, we're treated to a glimpse of what—or who—exactly gave that young girl the grace to one day stand as our nation's first Black First Lady. Mrs. Obama explains that as she grew up in South Shore, Chicago always focused on school, friends, and the events of the world, there was one comforting constant in her life: her mother, Marian Robinson.

Mrs. Obama writes about recognizing the ways her mother's calm and encouraging presence created room for her to simply be herself.

You'll be able to buy Becoming in stores and at amazon.com on November 13. But your first peek is below. Happy reading!

At school we were given an hour-long break for lunch each day. Because my mother didn’t work and our apartment was so close by, I usually marched home with four or five other girls in tow, all of us talking nonstop, ready to sprawl on the kitchen floor to play jacks and watch All My Children while my mom handed out sandwiches. This, for me, began a habit that has sustained me for life, keeping a close and high-spirited council of girlfriends—a safe harbor of female wisdom. In my lunch group, we dissected whatever had gone on that morning at school, any beefs we had with teachers, any assignments that struck us as useless. Our opinions were largely formed by committee. We idolized the Jackson 5 and weren’t sure how we felt about the Osmonds. Watergate had happened, but none of us understood it. It seemed like a lot of old guys talking into microphones in Washington, D.C., which to us was just a faraway city filled with a lot of white buildings and white men.

My mom, meanwhile, was plenty happy to serve us. It gave her an easy window into our world. As my friends and I ate and gossiped, she often stood by quietly, engaged in some household chore, not hiding the fact that she was taking in every word. In my family, with four of us packed into less than nine hundred square feet of living space, we’d never had any privacy anyway. It mattered only sometimes. Craig, who was suddenly interested in girls, had started taking his phone calls behind closed doors in the bathroom, the phone’s curlicue cord stretched taut across the hallway from its wall-mounted base in the kitchen.

As Chicago schools went, Bryn Mawr fell somewhere between a bad school and a good school. Racial and economic sorting in the South Shore neighborhood continued through the 1970s, meaning that the student population only grew blacker and poorer with each year. There was, for a time, a citywide integration movement to bus kids to new schools, but Bryn Mawr parents had successfully fought it off, arguing that the money was better spent improving the school itself. As a kid, I had no perspective on whether the facilities were run-down or whether it mattered that there were hardly any white kids left. The school ran from kindergarten all the way through eighth grade, which meant that by the time I’d reached the upper grades, I knew every light switch, every chalkboard and cracked patch of hallway. I knew nearly every teacher and most of the kids. For me, Bryn Mawr was practically an extension of home.

As I was entering seventh grade, the Chicago Defender, a weekly newspaper that was popular with African American readers, ran a vitriolic opinion piece that claimed Bryn Mawr had gone, in the span of a few years, from being one of the city’s best public schools to a “run- down slum” governed by a “ghetto mentality.” Our school principal, Dr. Lavizzo, immediately hit back with a letter to the editor, defending his community of parents and students and deeming the newspaper piece “an outrageous lie, which seems designed to incite only feelings of failure and flight.”

Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result.

Dr. Lavizzo was a round, cheery man who had an Afro that puffed out on either side of his bald spot and who spent most of his time in an office near the building’s front door. It’s clear from his letter that he understood precisely what he was up against. Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self- doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear. Those “feelings of failure” he mentioned were everywhere already in my neighborhood, in the form of parents who couldn’t get ahead financially, of kids who were starting to suspect that their lives would be no different, of families who watched their better-off neighbors leave for the suburbs or transfer their children to Catholic schools. There were predatory real estate agents roaming South Shore all the while, whispering to homeowners that they should sell before it was too late, that they’d help them get out while you still can. The inference being that failure was coming, that it was inevitable, that it had already half arrived. You could get caught up in the ruin or you could escape it. They used the word everyone was most afraid of— “ghetto”—dropping it like a lit match.

My mother bought into none of this. She’d lived in South Shore for ten years already and would end up staying another forty. She didn’t buy into fearmongering and at the same time seemed equally inoculated against any sort of pie-in-the-sky idealism. She was a straight-down-the-line realist, controlling what she could.

At Bryn Mawr, she became one of the most active members of the PTA, helping raise funds for new classroom equipment, throwing appreciation dinners for the teachers, and lobbying for the creation of a special multigrade classroom that catered to higher-performing students. This last effort was the brainchild of Dr. Lavizzo, who’d gone to night school to get his PhD in education and had studied a new trend in grouping students by ability rather than by age—in essence, putting the brighter kids together so they could learn at a faster pace.

With any game, like most any kid, I was happiest when I was ahead.

The idea was controversial, criticized as being undemocratic, as all “gifted and talented” programs inherently are. But it was also gaining steam as a movement around the country, and for my last three years at Bryn Mawr I was a beneficiary. I joined a group of about twenty students from different grades, set off in a self-contained classroom apart from the rest of the school with our own recess, lunch, music, and gym schedules. We were given special opportunities, including weekly trips to a community college to attend an advanced writing workshop or dissect a rat in the biology lab. Back in the classroom, we did a lot of independent work, setting our own goals and moving at whatever speed best suited us.

We were given dedicated teachers, first Mr. Martinez and then Mr. Bennett, both gentle and good-humored African American men, both keenly focused on what their students had to say. There was a clear sense that the school had invested in us, which I think made us all try harder and feel better about ourselves. The independent learning setup only served to fuel my competitive streak. I tore through the lessons, quietly keeping tabs on where I stood among my peers as we charted our progress from long division to pre-algebra, from writing single paragraphs to turning in full research papers. For me, it was like a game. And as with any game, like most any kid, I was happiest when I was ahead.

I told my mother everything that happened at school. Her lunchtime update was followed by a second update, which I’d deliver in a rush as I walked through the door in the afternoon, slinging my book bag on the floor and hunting for a snack. I realize I don’t know exactly what my mom did during the hours we were at school, mainly because in the self-centered manner of any child I never asked. I don’t know what she thought about, how she felt about being a traditional homemaker as opposed to working a different job. I only knew that when I showed up at home, there’d be food in the fridge, not just for me, but for my friends. I knew that when my class was going on an excursion, my mother would almost always volunteer to chaperone, arriving in a nice dress and dark lipstick to ride the bus with us to the community college or the zoo.

In our house, we lived on a budget but didn’t often discuss its limits. My mom found ways to compensate. She did her own nails, dyed her own hair (one time accidentally turning it green), and got new clothes only when my dad bought them for her as a birthday gift. She’d never be rich, but she was always crafty. When we were young, she magically turned old socks into puppets that looked exactly like the Muppets. She crocheted doilies to cover our tabletops. She sewed a lot of my clothes, at least until middle school, when suddenly it meant everything to have a Gloria Vanderbilt swan label on the front pocket of your jeans, and I insisted she stop.

Still to this day I catch the scent of Pine-Sol and automatically feel better about life.

Every so often, she’d change the layout of our living room, putting a new slipcover on the sofa, swapping out the photos and framed prints that hung on our walls. When the weather turned warm, she did a ritualistic spring cleaning, attacking on all fronts—vacuuming furniture, laundering curtains, and removing every storm window so she could Windex the glass and wipe down the sills before replacing them with screens to allow the spring air into our tiny, stuffy apartment. She’d then often go downstairs to Robbie and Terry’s, particularly as they got older and less able, to scour that as well. It’s because of my mother that still to this day I catch the scent of Pine-Sol and automatically feel better about life.